The NEXT THRILLING CHAPTER 9

- Who you calling stupid?

This is the ninth part of The NEXT THRILLING CHAPTER. I thought it was time for a change of pace, so it’s a short knockabout chapter with an exciting chase.

Since there’s not much that need be said about it, maybe I ought to take the opportunity to say a little more about how the serial as a whole came into being—and admit that I have a bad conscience about at least one aspect of it.

Making the serial was a ludicrous idea I committed myself to for a number of reasons. As Den Brock said, presenting his own response to what he saw happening, sometimes you just have to speak up, even if nobody listens.

Because silence is tantamount to complicity.

And if nobody listens—because, after all, why should anybody listen to me?—maybe all I was doing was saying to the future, “Here’s what I saw, I knew it was happening.”

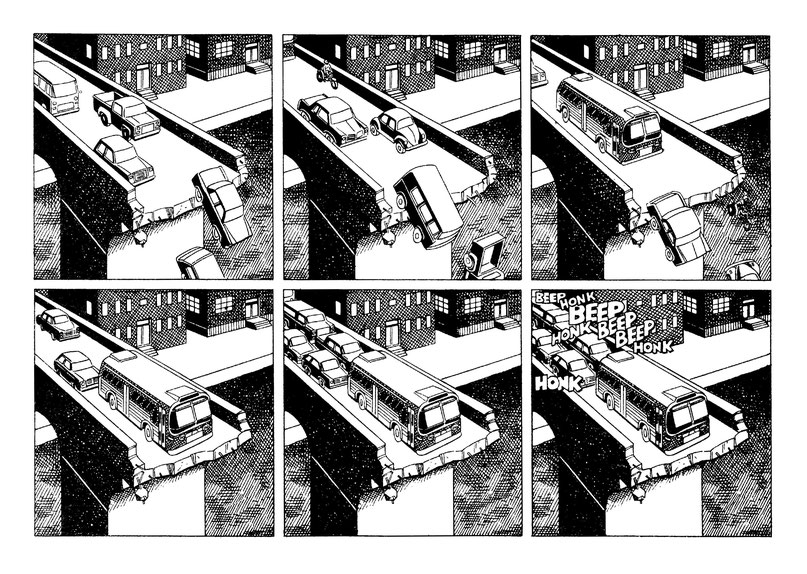

Because it’s easy to look back, with 20/20 hindsight, and be astonished people didn’t know they were headed for a disaster. And to anyone in the future who wonders why I made a movie serial instead of doing something about it, I’ll say, “Do you still misunderstand the situation?” In which case, let me offer into evidence a six-panel cartoon strip by Paul Kirchner (from around 1980) which I consider a profound comment on human nature:

I’ll also respectfully point out that I did what I could, with the limited resources at my command.

Yet these resources are not so limited. When I was a child, what appeared on a movie screen or television screen passed into the reservoir of memory, but could not otherwise be recovered or reproduced. Getting on the other side of a camera, in the hope of making something for a large audience, required a lot of determination and a fair bit of good luck, as well as somebody else’s money. We live in a different world now, and the odds have tipped in my favor, haven’t they? The tools with which to make the movie serial were at hand, the materials weren’t hugely expensive, and I have a distribution system at my fingertips that offers me a potentially worldwide audience. And I remember how I used to hear about the democratic potential of the internet, so what did I hope might happen when I tested that? Maybe something like this:

I make the movie serial, which warns against the consequences of a political party with a broad base and a long history throwing its weight behind undermining democracy in an effort to hold on to power. Somebody sees the serial and, recognizing the potential danger of a once-in-a-century breakdown of social order, shares it with a few others as a way of passing on the idea it’d be better if it didn’t happen, because, while it’ll give historians something to write about, it probably won’t be much fun to live through. And the others share it with other others, and when enough other people agree it’s something we don’t really want to happen, maybe it doesn’t happen.

I wasn’t hoping for much, was I?

Of course, the democratic potential of the internet also means we get to vote on whether we’d rather be entertained and distracted than have to think about serious stuff. If a sufficient number of people are taking seriously what’s happening, it obviously doesn’t take a piece of satire disguised as a movie serial to make them think we ought to do something about it. But who takes satire seriously these days? And, to be honest, when I made the serial in 2022, I was under the impression too few people were taking the situation seriously. In which case, wouldn’t it have made more sense to try to persuade people to take it seriously?

But I don’t have much of an inclination to try to persuade anyone of anything, possibly because I’m not very good at it.

Possibly also I’ve got some kind of a wrongheaded notion people ought to be able to make up their own minds. I always wanted to be able to find my way to my own opinions, and resisted being bullied or tricked into adopting the opinions of others, so I suppose I prefer to extend to others the same opportunity I want for myself.

At the same time, I don’t mind engaging in argument, and sometimes have strong convictions—as in this case, where it seems to me obvious that deliberate deception and a willful and dishonest embrace of fantasy are walking some of us toward the edge of a precipice, with the promise that, when we get there, we’ll be able to fly. I don’t expect to grow wings, so I feel some responsibility to point out we may be in for a hard landing.

But how to do it? There’s always a lot going on. Everybody’s chattering, and there are plenty of people with louder voices than I’ve got, and I’m not someone they’ll stop talking to listen to. If they did, I’d probably trip over my tongue. So I didn’t see much point shouting, or straining to get their attention. How often do you stop to listen to some nut, shouting on the sidewalk?

When I wrote the script, all I was trying to do was was overcome an inclination to reticence, and to express my fears and feelings about the political situation in a very direct way. Even if the intent was satirical, the challenge was to be entirely transparent and obvious in setting out the position I was taking. In fact, I was concerned the scripts were too obvious, so I tried to provide viewers with a few distractions and puzzles, over which they might imagine they’d triumphed as the simple and blatant statements in each chapter unfolded.

One place I thought I was being overly obvious was in repeatedly using images of the Zuggs from Buck Rogers (a thoroughly awful serial) to represent the army of mindless robots ideologically programmed by Donald Trump (with the aid of the media outlets that sustain him) to unthinkingly do what they’re directed to do—which is mostly give him their money, though some are invited to offer more. In the serial, the Zuggs are shambling, brutish creatures, fit only to serve the ruling class; and they are manipulated to support a usurpation of power. They are the caricature of a dull-witted mass, evidently incapable of thought or independent action.

And this is where I find myself suffering the pangs of a bad conscience, because, while there’s no doubt many of Donald Trump’s supporters are among the stupidest people on the planet, it makes me uncomfortable to say so. It’s disrespectful to call someone stupid, or to have contempt for someone who may be ignorant or experiences cognitive difficulty. I mean, what do I know? I may be passably articulate when left to my keyboard, but there are bright sparks out there who know more than I do, and could leave me tongue-tied and confused in a half-minute flat without breaking sweat. One reason Trump’s supporters love him is he plays to them as he’s playing them, reassuring them that their simple and thoughtless responses to his provocations are not only as much as might be expected of them, but are sufficient to show they belong to a body of righteous, right-thinking people.

Moreover, I’m unlikely to win anyone over by calling them stupid—though it’s thoroughly unlikely anyone I might wish to “win over” would ever be reading these words. Just in case, let me make it clear: if you’re reading these words, I don’t think you’re stupid. How could I? I don’t know you; and I consider it wrong to assume somebody’s stupid just because they belong to a particular group or class of people. On the other hand, if you happen to think Donald Trump has your best interest at heart, or cares about anyone other than himself, you might as well know that I think you’re wholly—and indefensibly—wrong.

And here I think I begin to understand what I find most difficult to accept, but plainly see: the flagrant stupidity of Trump’s most fervent supporters, that manifests itself when they’re confronted by evidence they’ve been conned. They’re defending themselves. Nobody likes to be called stupid.

I’m also uncomfortable because if I say Trump’s supporters are stupid, which I take to be a fact, it may taken to mean I’m saying they’re unintelligent. But stupidity is not lack of intelligence. Intelligence involves a set of capabilities which not all possess equally, but stupidity, whether in thought or deed, is something of which we’re all capable. To borrow an observation from J. A. Posner, stupidity is what happens when we work in our own shadow—when we decline to take care that things are what we take them for, and act without regard to whether the results of our actions may be beneficial, rather than doing us harm. A great many of Trump’s supporters are stupid, in this sense, because they are willfully and determinedly so, having been led to believe their stupidity is to their advantage.

Alas, no. It is to the advantage of those who manipulate them. Chapter 9 of The NEXT THRILLING CHAPTER posits a fantastic device that “amplifies and broadcasts stupidity.” Of course, in reality, there are a multiplicity of such devices.

Welcome to the global village.