36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

32: The case against Giraud

“At any rate,” he went on, “I can speak for myself: there’s an idea in my work without which I wouldn’t have given a straw for the whole job. It’s the finest, fullest intention of the lot, and the application of it has been, I think, a triumph of patience, of ingenuity. I ought to leave that to somebody else to say; but that nobody does say it is precisely what we’re talking about. It stretches, this little trick of mine, from book to book, and everything else, comparatively, plays over the surface of it. The order, the form, the texture of my books will perhaps some day constitute for the initiated a complete representation of it. So it’s naturally the thing for the critic to look for. It strikes me,” my visitor added, smiling, “even as the thing for the critic to find.”

This seemed a responsibility indeed. “You call it a little trick?”

“That’s only my little modesty. It’s really an exquisite scheme.”

(Henry James, “The Figure in the Carpet”)

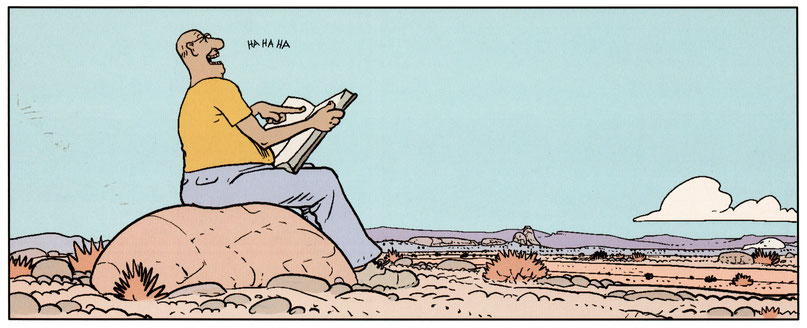

I’ve enjoyed and greatly appreciated my rediscovery of Giraud, but I’m not so devoted to his work that I don’t entertain the odd tremor of ambivalence. I don’t like everything he did; and what I like I don’t like equally. If I try to be a discriminating reader, not all of that discrimination may be justifiable; it doesn’t always constitute a judgment. Some of what astonished me four decades ago continues to glow so brightly that I might suppose myself permanently dazzled, and unable to see clearly. That other things have brightened while yet others fade suggests, on the contrary, that I don’t view everything through a mist of nostalgia. Indeed, my rediscovery of Giraud has been largely the discovery that, whatever the impact of Arzach and the Garage in the seventies, what he did afterward was by no means lesser work. I’ve been engaged and delighted by some of what he produced in each of the three succeeding decades.

At the same time, I know that admiration of Giraud’s work is by no means inevitable. I wonder if my vision is sufficiently clear to discern why he might be viewed less favorably.

While there may be reasons for a negative response, I’d like to begin by discounting one that ought not to be taken seriously:

Giraud’s career spanned something like half a century. In the field of Franco-Belgian bandes-dessinées he was already a noteworthy figure and popular artist by the time he began securing his place in history as Mœbius. He has been held in such esteem by critics, colleagues and fans that it may appear difficult for a reader to form a fair estimate of his achievement without being overwhelmed by the established fact of his greatness.

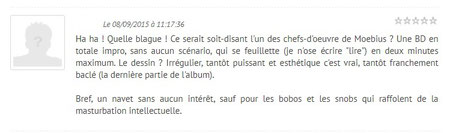

One solution is biblical: if thine eye offend thee, pluck it out. Last year I came across a brief post on a French site, at bedetheque.com, by someone apparently irritated by Arzach because (the book being wordless) he was able to scan it in a couple of minutes.

His conclusion? That admiration for the work was therefore no more than an affectation.

It’s not necessary, however, to insist that a positive response is fraudulent in order to acknowledge a contrary possibility.

In 1987, a reviewer reported that the first volume of Marvel’s series of books devoted to Giraud’s work “confirm[ed] what one has long suspected: Moebius is a bore” (Comics Journal #119, p.28).

Personally, I’d tend to be cautious about mistaking the discovery of my boredom for an objective fact about the thing I’m looking at. Even if I trace the cause of my boredom to some objective fact, it won’t substantiate the conclusion that boredom must be the inevitable result. Plenty of things bore me that excite or fascinate others.

The converse is also true. One problem in aesthetics is that every attempt to justify one’s enthusiasm as objective and necessary is bound to have only a partial, and perhaps a very local success. It often involves inventing criteria for understanding and appreciation that other members of the audience are willing to ignore or refuse to accept.

To propose that every response, being subjective, is therefore as valid as any other raises its own problems. There are varied contexts—personal, historical, social—in which a work of art is received that will affect how individuals respond to the work, and how they consider themselves in relation to other members of the audience. My attempt to say something about Giraud’s work rests, in part, on the simple-minded notion that my response to it, however bound up with my personal history, is unlikely to be utterly unique.

Obviously, I’ve been fascinated and engaged; but it doesn’t stop me knowing that what Giraud did as Mœbius might meet with indifference, or engender hostility or exasperation. In venturing a few guesses at why, I’ll continue to chart my own course; but some part of what I’ve come up with is anticipated by that review in the Comics Journal, so credit where credit is due.

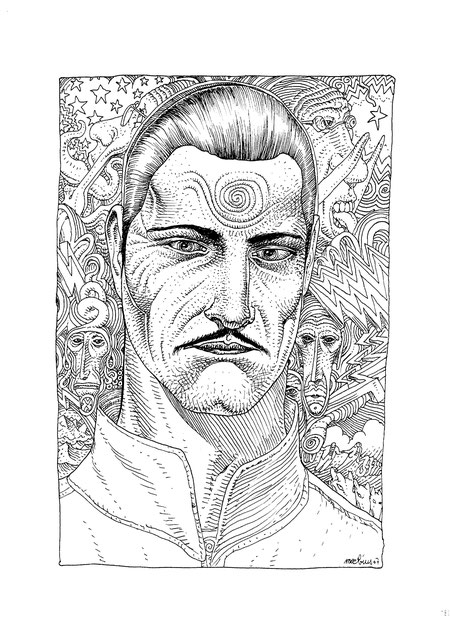

It may seem odd (or it may be perfectly obvious) to say that one reason Giraud’s work might fail to interest some readers is that he’s essentially a realist. He leans toward caricature, and relaxes to sketchiness, but rarely strays far from his center. Almost everything he does is based on a competent, well-ordered approach to illustration. What he draws has weight; it occupies space. There are many artists—including many less capable, and more limited—whose style is more distinctive, whose work abrogates and transforms the real in more eccentric and eye-catching ways. It’s probably not fair to judge Giraud on the basis of such a comparison, but it’s surely legitimate for a reader to prefer one style over another. If you’re looking for visual excitement, Giraud’s style—insofar as he has a style—may strike you as rather “quiet”.

I’ve succumbed rather easily to much of what Giraud has to offer, so it’s pretty obvious I’ve no real trouble accepting his style. I do so mostly without thought or judgment, and, if I take pleasure in the pictorial surface, my attention extends also beyond it—which means, I suppose, that it’s not so much my attention as my synthetic imagination, putting together the building blocks he sets in front of me. This is a matter of enchantment, which, in my experience, is not susceptible to legislation. If I’m enchanted, I give my attention easily; willingly, and with pleasure, I do the work of making sense of image and story. Deliberate attention is, of course, possible, but is often less open, less free. If you’re not enchanted by Giraud, nothing I’ve written here is likely to be persuasive or convincing.

I could invent other reasons why someone might not enjoy looking at Giraud’s work, but I suspect I’m on firmer ground if I broaden my inquiry and consider what he draws, rather than how he draws. To put it at its broadest: Mœbius is essentially a fantasist, and fantasy is not to everyone’s taste. He worked in a genre that is often childish, rarely serious, and either misrepresents the world we know or replaces it with make-believe. Even those who tolerate or have a taste for fantasy are likely to have their preferences.

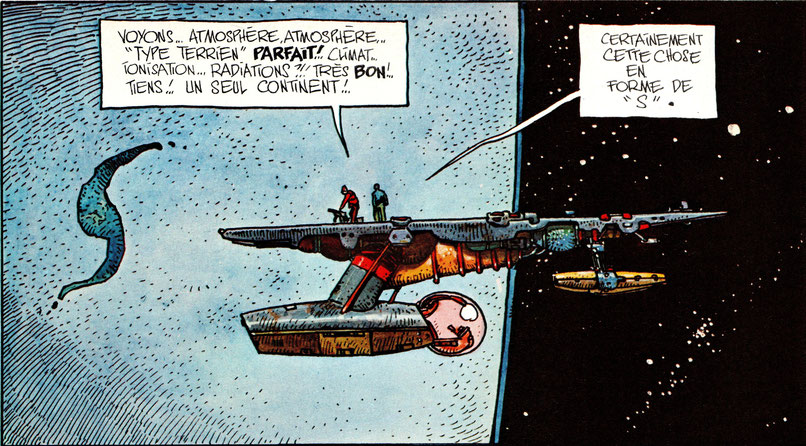

Mœbius is associated predominantly with science-fiction. It’s the branch of fantasy that pretends a rational basis for its deformation of reality; but the genre has long allowed considerable latitude with regard to just how rational that basis needs to be. Magazines, comics and movies each negotiate their own allowances with their sometimes overlapping but far from identical audiences, and Giraud’s sf is rather light on the science.

This has largely been the rule in comic strip sf, rather than the exception. Giraud’s sf might bear comparison with Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon—a fondly-remembered classic that turns out, on close inspection, to be thinly plotted, repetitive, and barely science-fiction at all. To paraphrase the reviewer of Giraud mentioned above, at six panels a week this was not so clear. But it may be missing the point, as much of Flash Gordon as of Giraud’s fantasies, to complain that they’re “underwritten”. The plot of the newspaper serial served as little more than a framework for the what-happens-next? that opened a gleaming half-page window, every week, onto a world of imagination that existed partly on the page, but largely in the space of expectation before the next episode came along.

Of course, if story is not always the most important thing in a comic strip, this hardly counts as a defence if what you’re looking for is story. Readers new to Mœbius may be disappointed to discover that, during the period of his glorious emergence (1973-79), most of Giraud’s shorter strips—and there really aren’t a huge number—might be described as vignettes, anecdotes, incidents or gags. And to identify the nearly one hundred pages of the Garage as a surrealist game—a kind of one-man narrative corpse—won’t make it more palatable if you like your stories to make sense.

The longer works of his later period are more coherent in tone, more self-consistent in style, and less obviously whimsical in narrative development; but whether it makes them more substantial, or whether, ultimately, their development may be considered coherent, are questions open to argument. Is the fifth book in the Edena cycle (SRA) the necessary fulfillment of the story begun in the first (Upon a Star)? Almost certainly not. Are Burg’s motives and intentions consistent, as depicted in the second, fourth and fifth books? In view of how obscure his motives are, I’m not sure it’s even appropriate to ask the question. Does it matter? I think it does, but make up your own mind.

Of course, I’m now entirely reconciled to lightness and looseness in Giraud’s stories, but a sense that they lacked substance may be why, at the end of the nineteen-eighties, when I had an opportunity to see the work collected, I chose instead to look away. I didn’t find it boring and forgettable, like the reviewer in the Comics Journal, but I thought I’d exhausted what I’d read. There wasn’t enough more—and there wasn’t enough in it—to hold my attention.

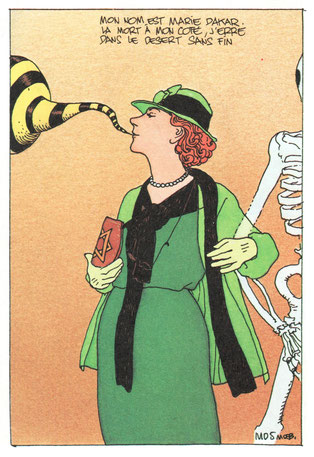

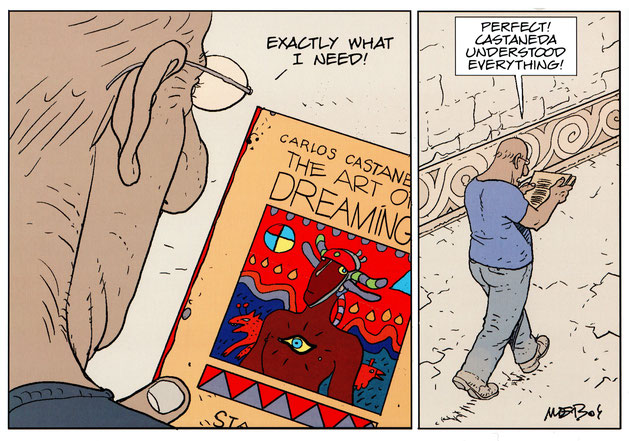

There’s also, let it be admitted, more than a whiff of crankiness in Giraud’s work, particularly his later work. Upon a Star rather depends upon accepting and being enchanted by the notion of submitting to the influence of a higher power—a higher power which, in the story, remains entirely mysterious. The sequel begins by reflecting Giraud’s contemporary fascination with a change of diet. Tarot cards recur throughout his works, and if at first I wondered whether references to Carlos Castaneda in Inside Mœbius might be ironic, I’m not wondering now.

Giraud was not exactly a child of the nineteen-sixties (he was thirty in 1968) but he was receptive and responsive to the cultural explosion of that period, and a decade later was beginning to follow a path of spiritual evolution. His works rarely amount to propaganda or didacticism, and presume no commitment to an ideology or belief-system; but if you have a strong antipathy to the free-spirited and sometimes woolly eclecticism of the “new age”, you may find signs enough in Mœbius to prove off-putting.

Something else might appear to sum up and “explain” some of the points raised above, and I’d like to approach it with the assistance of the review in the Comics Journal I alluded to earlier. But it’s only fair, before quoting from it, to make two things clear:

One, the review was mainly concerned with a story so light as to be judged almost void of content. With hindsight, I might see it as the rebirth of Mœbius, after a period when Giraud had tried to rebrand himself (as “Jean Gir”) and relegated “Mœbius” to doing slick but derivative visuals for The Incal; but I doubt I’d have made much of Upon a Star if I’d read it back in 1987.

Two, the reviewer had already given up on Mœbius: “I stopped following Moebius’s work because of a notion that, like pot, it might be destroying my short-term memory...” Now, I’m not sure he was indicating he’d given up smoking pot for that reason, or whether, irritated by Mœbius, he was only drawing a facetious analogy; but, in any case, Giraud’s

oblique, underwritten fantasies ... were often difficult or impossible to understand, and—far more damning—to remember. Like a dope-induced insight, ten minutes later you were unenlightened again...

Possibly this translates to the implication that someone would have to be stoned to enjoy Giraud’s strips, and that’s obviously wrong. Alternatively, it might reflect the proposition that, however much fun they might seem while reading them, a closer and more careful inspection will reveal them to be without value. That, at least, might be argued, though the conclusion would depend on one’s criteria of “value”. More broadly, it might be counted a dismissal of Mœbius as a particular case belonging to a general class whose dismissal hardly needed to be argued—of essentially self-indulgent and empty works. The key point, however, is the association with dope:

Any three pages [of Upon a Star] ... are nicely wonky. But if you’re wonky for long stretches of time without modulations, you turn into Cheech and Chong at Vegas...

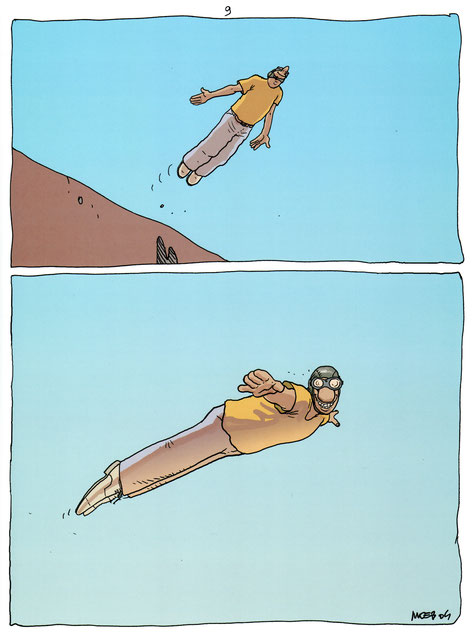

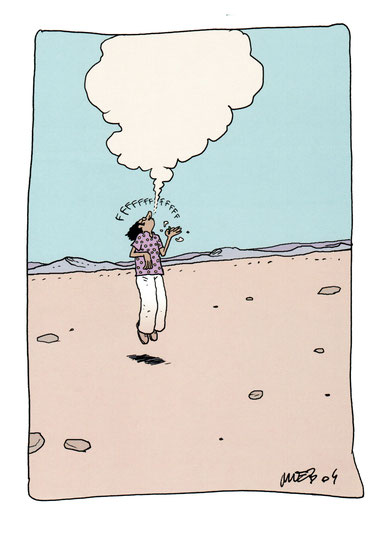

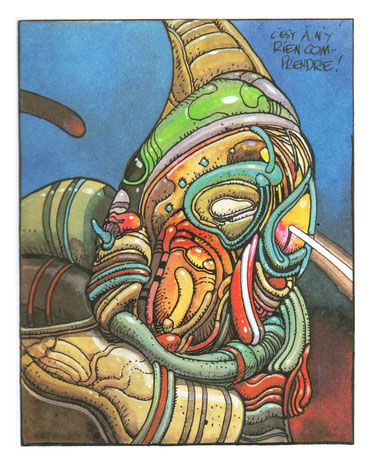

And perhaps it’s a point more acute than I recognized at the time. In his memoir, Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double, Giraud wrote how, when working on Arzach, he was uncertain of what would come next and “en plein vertige” (histoire p.21)—in the midst of dizziness or thoroughly giddy (though these translations are inadequate, forgive me). As an artist he wished “to be free in spirit, to know no bounds”, and, concerning Le bandard fou, one of the first stories he did in that spirit, he wrote that

It expresses an emotion, like “I don’t know what I’ve done, but I must continue. I don’t know where I’m going, but I must go on.” I think the reader feels that. I was not seeking to deliberately put these theories into practice. I was only doing it because I experienced great pleasure in doing so...

(afterword to “The Horny Goof”, MŒBIUS 0)

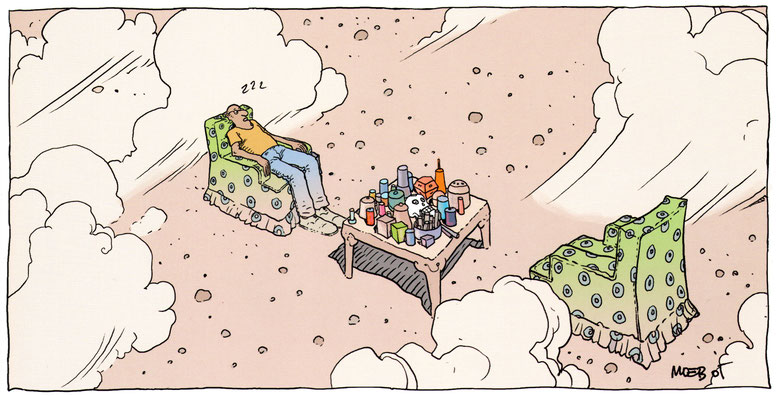

“The artist who works in such a way,” he later acknowledged, “is very vulnerable, easy to caricature” since it involved “something like a total loss of common sense” and indulged “a tendency without restraints, without inhibitions, toward a nearly shameless outpouring.” He repeatedly advertised it as an altered state of consciousness—“a sort of light trance... [a]n oracular state...” (histoire, pp.21, 163, 167)—and, for a long time, his method of attaining this state involved smoking cannabis:

Grass was for years an essential anchor: a door open to another reality. A working instrument, a conceptual tool, the key to prospecting despite its dangerous aspects and the possibility of dependence... This was already a deviation from my intention, which was to attain something higher: a legitimate impulse, profoundly human. Instead of getting there by the patient work of culture, of education, of artistic self-discipline, which is not given to everyone, it’s possible to get access more quickly, more strongly, and at will. At the risk of falling prey to a generalized sensory imbalance...

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double, p.171)

If what he wrote in 1999 suggests an ambivalence about cannabis, at a period when (not for the first time) he was considering giving it up, it was by no means a repudiation. He recalled discussions with Nikita Mandryka, during which they

erected grand theories on this “psychedelic” capacity. The word means nothing today, but it recalls well the artistic manner of the seventies. The issue consisted in attaining a creative ecstasy. A sensation that doesn’t have its place in the European tradition. Or is on the margins where it is systematically stigmatised, even sanctioned... From Joris-Karl Huysmans to Michaux, and well before them from Teresa of Avila to Saint John of the Cross, artists and mystics have revealed how poetic or religious fervor may lead to a divergence from reality. I refuse to integrate christian mysticism, any more than I wish to use alcohol to enter into a mediocre form of expiation, or tragic martyrdom. But grass, poetry, whatever launches the imagination like a flying wing takes me where I want to go.

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double, p.168)

So if you care to dismiss the work of Mœbius as colorful but empty productions fuelled by mind-altering drugs, the evidence is there to be had.

All this admitted, this is hardly the place to mount a defence. With three Arzach “stories” behind him, he wrote,

There’s no reason for a story to be like a house with one door for going in, windows for looking at the trees and a chimney for the smoke... One can very well imagine a story in the form of an elephant, a field of wheat, a dying match.

Or possibly one can’t. In what way might a story be like one of those things? It’s an appeal to the imagination, and if it’s not the way your imagination works, it won’t make a lot of sense. All Giraud was insisting on was an allowance to pursue stories, to find stories, to make stories not constrained by commonplace expectation. In the seventies, he’d seen both poles of the American underground comix, countercultural humor and unbridled fantasy; he wrote later of the prospect of freedom they advertised:

The great American artists – Crumb and Corben at the head – have opened up for us a new field of spirit. Spirit breathes in a new space of perception and expression that nowhere relies on a story...

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double, p.168)

And he wrote of finding ways to that new realm of freedom:

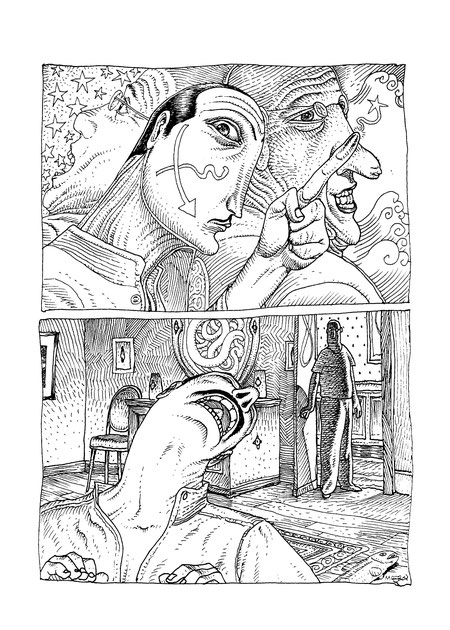

When I work as Moebius, I open myself to the sole necessity of being there, in the moment... I no longer exist: my hand becomes autonomous...

... Something other acts, speaks, draws which responds to another dimension. An intimate infinity. The stranger lives in us, strangely familiar, pregnant with an infinite virtuality of creation. All spirituality takes root in this free space, this internal black hole from which comes the matter of art.

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double, p.175)

If you’ve no experience of this, what Giraud wrote may sound woolly and fantastic. Those who recognize it may differ on how to characterize it. I tend to think of it as an innate human capacity, and anyone who works creatively, or with craft, will probably know that work engenders a familiarity of feeling that derives from practice, but is not so easy to express or explain. This is not news: in Chuang Tzu (or Zhuang Zi) there’s a wheelwright who can’t say how he makes a wheel. In another passage a swordsmith explains his skill by saying,

The taste for forging swords came to me when I was twenty... I apply myself exclusively to that... Whatever one does, when one does it ceaselessly, it ends by becoming unreflective, natural, spontaneous...

It is not a mystery that what we learn by doing is difficult or impossible to adequately convey by means of words. But when the act of creation has no preconceived object—such as a wheel, or a sword—to aim for? Out of what does the unexpected form arise?

I couldn’t do it by drawing, but I’ve watched it happen under my fingertips—more, it would appear, as spectator than participant—when writing. Very likely those who channel the wisdom of spirits and angels are tapping into this strangely familiar and intimate space of creation—and either giving credit where credit is due, or fooling themselves. Take your pick. Some musicians who improvise may have a similar experience; and Giraud’s facility in drawing was such that I’ve little doubt he could pursue his creative effort while paring away his deliberate intention.

A story is—apart from whatever else it might be—a mechanism for harnessing the attention of its reader. Some readers like to have a bit between their teeth and be ridden, as in a race. If the stories of Mœbius are by no means complex, and probably not incomprehensible—unless you insist on reading them while stoned—nevertheless Giraud wasn’t determined to treat the readers of his fantasies as horses were treated in Blueberry:

My job is to be internally free... And my duty is to express this through my drawings...

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double, p.28)

What he wrote about the elephant, the wheat field and the match was printed in Metal Hurlant #4. Two issues later, the first installment of the Garage appeared.