36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

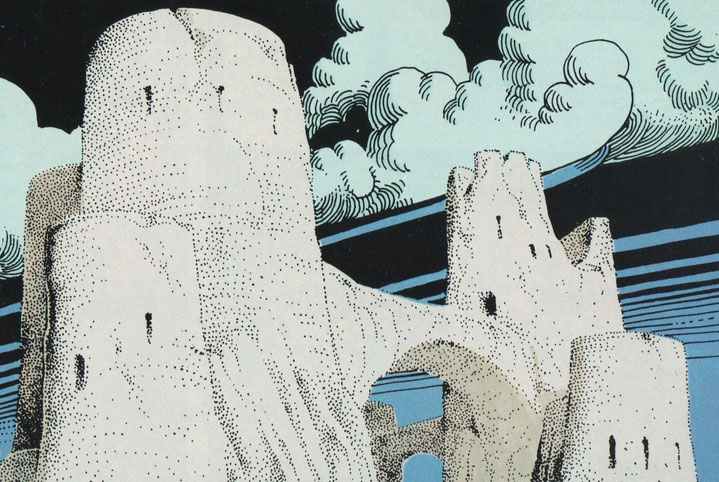

6: A castle by the sea

To the left, away from the sea,

Four children in a group are having fun

Furiously digging a hole in the sand;

Each of them is equipped with a spade...

(Raymond Roussel, “The View”)

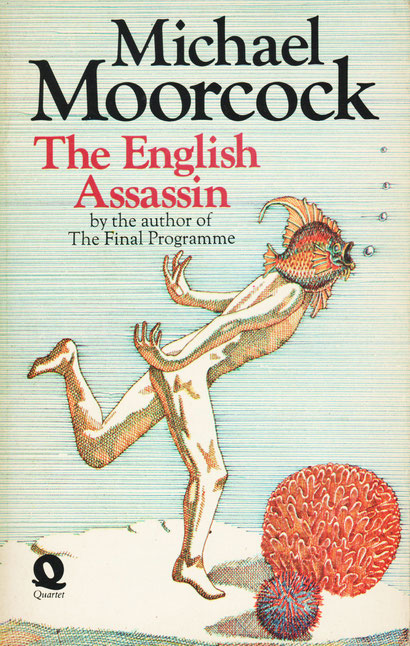

“I’m not sure I believe in accidents, as such,” says Catherine Cornelius, toward the end of Michael Moorcock’s The English Assassin.

She’s sitting on a deckchair on a beach, alongside her brother, Frank, and her mother, Mrs Cornelius. Out to sea, on the horizon, is a boat, possibly a warship. Nearby, four children are building a sand castle—or, to be more precise,

an elaborate sand palace, with turrets and towers and minarets and everything. They were digging a moat around it...

(Moorcock, The English Assassin p.222)

Now, I’m not sure what (if anything) the work of “the great Moorcock” meant to Jean Giraud. Giraud’s friend, Philippe Druillet, had illustrated Elric; Moorcock’s written worlds of fantasy chimed with Druillet’s dark and exotic visual elaborations. Giraud’s appropriation of Jerry Cornelius appears to have been far less deliberate. Indeed, it seems clear he had no intention of beginning a serial featuring Moorcock’s ironic and unstable protagonist. It began with only a playful reference to Cornelius in a two-page gag.

The whimsical deployment of names in absurd relation to an assortment of cartoons and illustrations is something that may be discovered throughout the work of Mœbius...

... but, responding to Jean-Pierre Dionnet’s request for a continuation of “Le Garage Hermétique de Jerry Cornelius”, Giraud took hold of the whim, immediately and recklessly hauling Jerry Cornelius and his late father onto the first page of episode 2—albeit without picturing either of them.

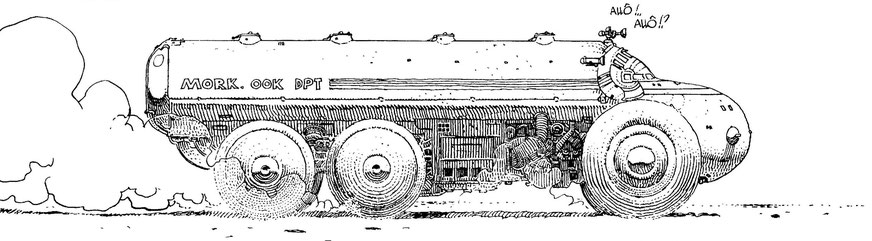

The elder Cornelius had been dead since before the beginning of Moorcock’s first Jerry Cornelius book, The Final Programme. I’ve already pointed out that his corpse was subsequently removed from the Garage; and his part in designing the cableur on which engineer Barnier was working was a thing of no consequence. Jerry, on the other hand, provided the motive force behind the developing action, as Barnier, panicking, prepared to flee in fear of his return.

In the following episode, it began to become apparent that the world of the story had been invaded, and that Cornelius was involved in the invasion. Giraud advertised that Cornelius would lay a trap for the Major’s spy, but, on this point, it’s probably fair to say Giraud was mistaken. On the other hand, Cornelius was an invader—or, at least, an outsider—in the world of Giraud’s invention. As such, he presented a problem.

Giraud deferred a solution by relegating him to the margins of the story. Admittedly, those margins were broad, and the photograph featuring Cornelius in episode 5 is memorable and imposing; but for two years that photograph declined to put on flesh; and the individual who’d communicated his concern to Jasper in episode 2 had nothing more to say for himself.

Michael Moorcock once said that the Jerry Cornelius of Le garage hermétique was not his Jerry Cornelius. It’s an observation that’s unarguably quite correct; but it led, unfortunately, to Jerry’s assassination, in the English of the 1987 translation. Sensitive to the possibility he’d misused the character and offended the author, Giraud permitted the alteration of his name from Jerry Cornelius to Lewis Carnelian. (In France, happily, Giraud’s Cornelius retains the name he adopted in 1976.)

But if Grubert’s would-be nemesis was not Moorcock’s fashion-conscious vampire, and had been imported into a world far from that character’s natural milieu—an apocalyptic and war-ravaged twentieth century—it may be that Giraud’s Garage nevertheless reflects and responds to the playful and transgressive mutability of the Cornelius stories. Several details might be advanced in support of this rather half-assed critical thesis, but—let me be honest—wouldn’t it be simpler if I accepted that Giraud’s dedication of MAJOR FATAL to Moorcock, in 1979, was more of a diplomatic (and apologetic) footnote to a work that flagrantly takes the name of Moorcock’s “hero” in vain?

Besides, why should I feel under any obligation to explain and justify an influence, or a profound creative debt, for which I have next to no evidence? (There may be testimony out there, in some interview or article; my researches have not been exhaustive.)

On the other hand, I did, after much hesitation, give in to the temptation to revisit the first three Cornelius books; and, as a result, I’ve discovered a more precise and intimate reason why Giraud dedicated MAJOR FATAL to Moorcock.

Let the reader proceed now with caution. Critics who operate by comparing works of art may assign to one an influence on another, where in point of fact both were influenced, separately, by a common original. Alternatively, the works may be similar because they are variations on a theme—independent inventions based on an underlying generic grammar. It’s not unknown for the critical argument of influence to be undone by a demonstration that the artist who was influenced could not possibly have encountered the work supposed to have done the influencing.

Since the sufficiency of evidence required to establish the truth of my discovery is lacking, let me frankly lay it before you as a thing to be doubted. It’s not a wilful or deliberate invention, so much as an entirely genuine (if questionable) perception of something that might have been possible. Let those who may, consult the Akashic record in order to attest its veracity; otherwise it may not be demonstrated. But there is much in the sections to follow of dry fact and measured observation. Allow me, first, a moment of irresponsibility:

I don’t know exactly when or where this happens. It can’t be before 1972, and I’d prefer to imagine it takes place before the end of 1975. Giraud is reading Michael Moorcock’s The English Assassin. I suspect he’s reading it in English, because, as far as I know, a French translation was not published until 1981. I don’t know if he’s reading it, or skimming it—but I see him reading the last chapter with attention. It takes place on a beach, which is for Giraud (as he wrote later) a kind of borderland, a margin of consciousness on the edge of the great deep of the unknown.

The chapter is called “THE SEASIDE”. Frank and Catherine Cornelius, along with their mother, Mrs Cornelius, have arrived at this unidentified beach. The weather’s hot; they settle in deckchairs. Nearby, some children are building a sandcastle. As Mrs Cornelius watches, the sandcastle continues to grow. It’s huge, impressively (and preposterously) detailed: “She could almost have believed it was a real castle if she’d seen it in the distance.”

As Giraud reads that line, he experiences a moment of pleasure. The momentary and fantastic uncertainty concerning the scale of the castle reminds him of the first science-fiction story he contributed to Pilote, back in 1971. “The Artefact” also featured a castle rising from the sand, and, briefly, Giraud is almost pleased to imagine Moorcock read his story, and is making a reference to it. He dismisses the thought almost at once, but it seems, nevertheless, that his little story is validated by Moorcock’s variation on it. Giraud has done science-fiction illustrations for Galaxie, and for Opta’s limited edition hardcovers, but he’s written little. Nevertheless, however modest his efforts, here is confirmation that he exists in the same space as the writers he’s been reading since his father introduced him to science-fiction in the fifties.

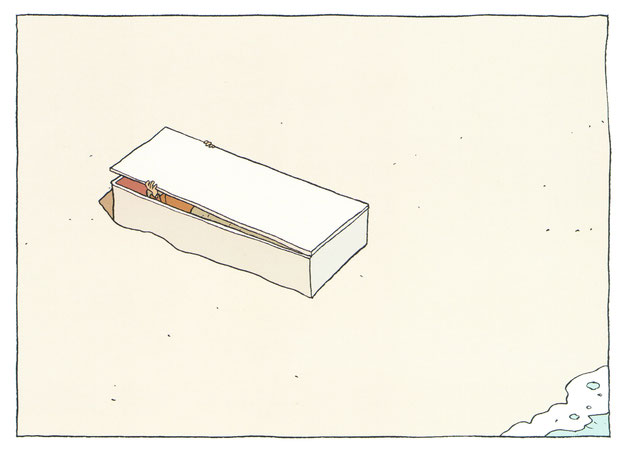

More might be said about the coffin unearthed by Catherine, as she digs down into the cellar of the castle—yes, the sandcastle has a cellar—but I intend to leave Giraud to his reading. Anyone who wants to draw a line from the coffin Catherine finds to the coffin that washes up on the beach in Giraud’s rather wonderful “Dying to See Naples” (2000) is free to do so, but I’ll forego the opportunities of fiction, and hope to encompass the remainder of the Garage with a more determined measure of sobriety and seriousness.