Our Conversation with Mars

by Felix Bowman

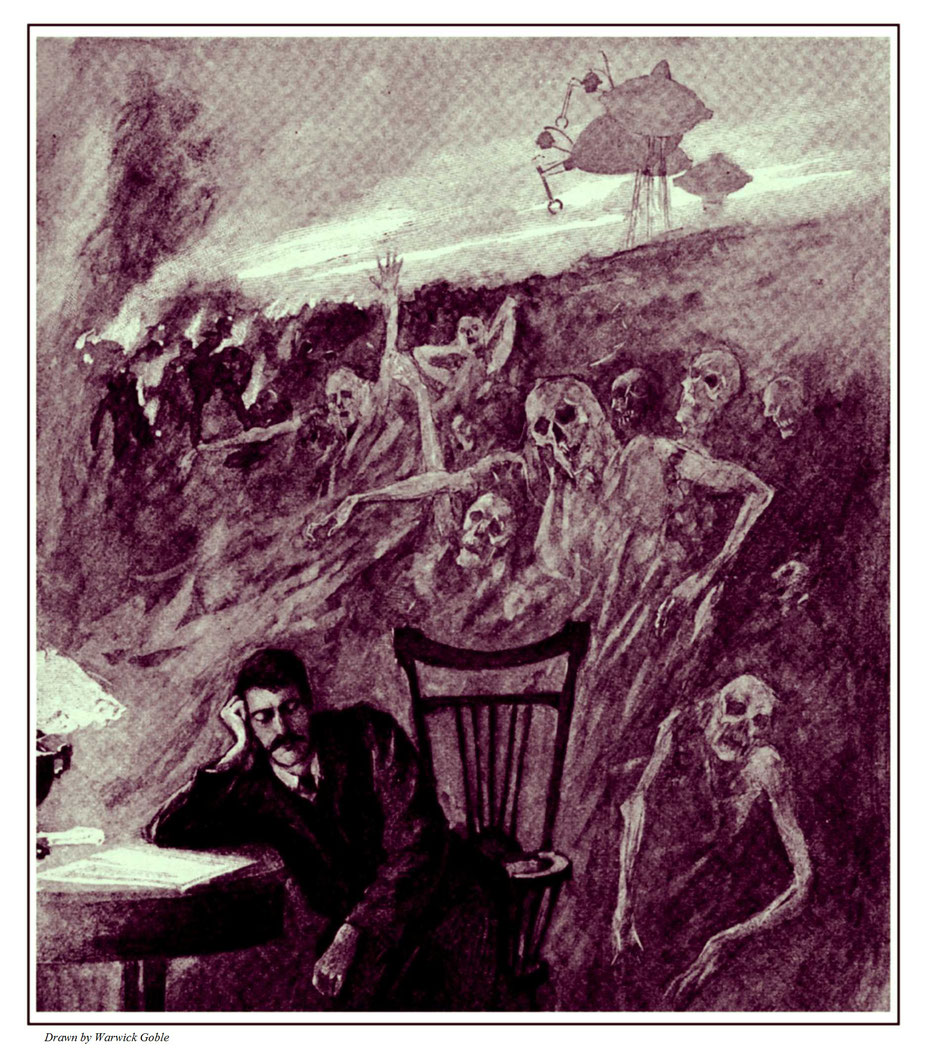

Not long after the Second World War—we’d gone back to fighting among ourselves, obviously—the Martians sent a message to the newly formed United Nations. Truman, the American president, stated, in no uncertain terms, that any landing would be viewed as an act of aggression. They would not, this time, be allowed to unscrew their cylinders or assemble their hellish machinery. Nobody felt very much like making up back then. For their part, the Martians put it about they were disinclined to venture a second time on to our “disease-infested planet” and we heard nothing more; but concerns they might have established contact behind our backs with the communist countries fuelled international tensions—lots of little wars and four decades getting ready for the big one. This came to a head with the Strategic Defense Initiative, a plan to shoot both Martian and Russian missiles out of the sky before they reached American soil. Then the Russian Empire began to collapse. That persuaded some the Martians were out of the picture. The attack on the World Trade Center in 2001 raised suspicions they might still be acting as covert sponsors of terrorism, but not everyone was convinced. You don’t need Martian interference to explain what people get up to sometimes.

It was a surprise, therefore, when, in the autumn of 2016, everyone got a message in their mail advising them the Martians were in touch with three representative governments, and hoped to establish cultural and trade relations. A bit awkward for the Americans in an election year, but it was confirmed that they, the Chinese, and the Russians were involved. It became clear the Martians had made public, if not full, disclosure a condition of dialogue, and these governments had been chosen to act as intermediaries on behalf of the whole planet. Some commentators suggested the Martians’ grasp of changing geopolitical dynamics was somewhat conservative. Where did it leave the rest of us? Reading the carefully worded joint statements following each communication.

I’m Mark White, by the way. Maybe you’ve seen me making a prat of myself on television, but you haven’t heard the whole story. When this all started, I was a researcher at the London Institute for Martian Studies, based at Primrose Hill, so naturally I was following it closely. I’d no reason to suspect, however, that one day I’d have the opportunity to talk with a Martian. Renewed interest in my subject got me in the news. I had my doubts about the Martians’ friendly intentions, and wasn’t shy of saying what anyone with half a brain already knew—that the politicians hadn’t a clue when it came to dealing with them. So it was something of a surprise when I was called to testify before a committee reviewing the possibility of holding exploratory talks with the Martians.

I wasn’t the only one thought it might be an idea to keep them at arm’s length, but it was soon obvious, no matter what the politicians said about caution, and the best interests of the peoples of our planet, that the talks would go ahead. The Martians left some of their toys lying about after their last visit, and the bright boys reckoned we were readier now than we were then to learn something. Since the Martians were determined to make contact, the consensus was it was better to try to manage the exchange than refuse it outright. Parties to the potential dialogue were also locked into it by a concern their withdrawal might put them at a disadvantage with respect to their neighbours here on Earth. Whether the Martians had been forced to make their approach because they were desperate was an open question, and whether we’d lose more than we might gain by allowing them to expire was a topic for public discussion. But if the Martians were running out of time, it was possible they’d been running out of time for about as long as we’d been wearing clothes.

The Martians showed no signs of impatience as the wrangling dragged on, but made it clear they wanted face to face talks—and they didn’t mean faces on a video screen. They said they understood the potential difficulty of a close diplomatic and political encounter involving creatures so dissimilar, but suggested that if they—and we—did not confront this difficulty, it might result, at a later stage, in a derailment of negotiations. Their situation was critical, they insisted, and they could no longer afford to hide.

This led to a robust statement that the peoples of Earth would not be railroaded into being told what form the talks would take. The admission from the Martians that they had been “hiding” was counted against them.

Both sides accepted there was no question of a Martian landing on Earth. Neither was there any need, the Martians pointed out, for delegates from Earth to travel to Mars. A fully observable simularium might be built here, and this would allow a virtual conference. The principle was not immediately accepted. Not least, the distance between the planets presented a problem. A time delay involving radio signals might render exchanges rather cumbersome. While there was something to be said for a formal diplomatic style—speeches and statements separated by long pauses for consideration—there were concerns it was a style that might suit the Martians’ propensity for calculation. In the event, they forced our hand by presenting us with plans for transmitters and receivers that would eliminate the delay. Aside from its use in the proposed talks, the advantage of this system to any program of remote exploration was at once apparent to all—though the Martians declined, for the time being, to explain the principle. We could build the things, but couldn’t figure out how they worked.

And there’s no question everyone got a lot more nervous. I remember a security briefing, at which Nelson Garry said something like, “The Martians admit their observations of Earth have been extensive, but we can only guess at their powers of resolution. For all we know, nothing we say is spoken under a guarantee of privacy. We have little choice but to proceed with the utmost care—and as though their attention to our deliberations is of no moment.”

Security of the simularium was a separate matter. The technicians worked to ensure full transparency. A buffering delay of 1.5 seconds was introduced. In addition to real-time overview of all aspects of the process, any violation of agreed signalling protocols would trigger an automatic precautionary shutdown.

By that time I was very much in the loop. Whatever the Martians wanted, we wanted to gauge whether full diplomatic contacts might safely be opened. The set-up would be tested by having a number of delegates enter the simularium in order to confront the Martians. The human delegates would have no political authority, but the encounter would be observed and analysed by a large team of experts. Broad international representation was essential, and there were strongly divergent points of view. The Institute had a worldwide reputation, so I had a close-up view of some of the negotiations. But reputation doesn’t translate to political clout, and I was a bit miffed when I was invited, in 2023, to be one of the two European delegates. The other was a French cultural theorist, Bertrand Mevel. I’d always reckoned it wasn’t more than an outside chance I’d get a place in the first rank of observers—but I thought I merited at least second-level consultant. The delegates, so called, were little more than rats in a maze.

But somebody had my number. I’d been interested in the war since I read about it in my teens. I’d spent my adult life immersed in the subject, and the more I thought about it, the more the idea of sitting across a table—all right, a virtual table—from a Martian, and being able to talk to a Martian, seemed an unmissable opportunity. My position at the Institute would be unassailable, because who else could say they’d talked with a Martian? Of course, the other side of it was what if I’m one of the monkeys gets caught when the Martians hold out a banana? But, taking it all into account, how could I say no?

One of the first things I was asked to do was shave off my moustache. “We’ve noticed, Mr White,” said one of the virtual technicians—a small, cold-eyed woman by the name of Boxell—“you have a habit of smoothing down your moustache with your right hand, and we’d like you to break this habit.”

I didn’t feel inclined to oblige her. “Do I have to?”

“In simulation,” she explained, “tactile sensations are somewhat simplified. If, when stroking your upper lip, you discover your moustache is not there, this may provoke feelings of dissociation. Things will go more smoothly if you’re not surprised in this way.”

I was to be interviewed on television about my small role in establishing interplanetary relations, and the producer, Warren Evans, was unhappy about the upper lip. “Why did you do it?” he kept asking me. Seems he had a point. Analysis of reactions to the broadcast suggested the well-known expert on the Martian war—myself—was not only less recognizable without the moustache, but viewers regarded him as being less trustworthy. It nearly cost me my position on the project, until I pointed out that whether I looked trustworthy would matter about as much to the Martians as a thoughtful expression on the face of a pig matters to a farmer.

Anyway, my public image was no longer under my control. There followed two years of intensive preparations for the encounter. I let out my flat in London and relocated with the rest of the delegates to a high-security training camp in Virginia. The actual simularium was being built in New York.

“Of course, you won’t need to shave when you’re in simulation,” says Ms Boxell. Dawn didn’t like me any more than I did her. I got the impression she resented there were no women among the delegates. Not my decision, but, as it happens, the right one. There’s only one Martian sex. We opted for parity—and you don’t put women in the same room as a thing with tentacles. “On the other hand,” she reassures me, “you’ll be in full control of evacuation. There will be private cubicles. These episodes will not be broadcast, but they will be monitored.

“You won’t be hungry,” she says. “We’re in control of nutrition. But you’ll be in-sim for about three weeks, and if you don’t eat, you’ll probably get anxious. The menu is fully synthetic. It’s designed to minimise cultural issues surrounding the consumption of food—a delicate issue in the circumstances. But the textures and flavours will always be surprisingly familiar.

“Also, you’re unlikely to feel tired, but you will need to sleep. There may be long sessions. We’ll be monitoring to ensure you’re not overextended. There will be opportunities for relaxation and—within the limits of the simulation—privacy. Bunks are set in a secure area. To put it simply, you’ll be sleeping here on Earth, but return to consciousness will trigger reincorporation in conference reality. You won’t be trapped, though. Any discomfort and you need only excuse yourself, stating that you wish to leave the simulation. Naturally, we’d prefer you avail yourself of this only in case of emergency, but we can have you withdrawn at any moment. We’ll be watching all the time.”

Sometimes I wondered if I’d ever be able to open my mouth without feeling like a ventriloquist’s dummy. A year or so in, I raised this with one of the psychologists.

“No, Mr White, not at all. No,” said Dr MacGregor, “you know as well as we do that we don’t want a puppet. We want you to be yourself. At the same time you need to be prepared. There’ll be in-sim videophones, and you’ll be debriefed by videolink after each session, but”—he leaned forward. He was about forty, and looked as if he was just out of high school—“the purpose of the exercise is to find out how human beings function in dialogue with the Martians. Whatever the value of your opinions, your reactions—which we’ll be monitoring closely—will tell us more. Nothing, ultimately, will be decided by what you say to the Martians, but, at the end of the day, we’ll know where we stand.”

I found the sim-suits kind of off-putting, but once we were hooked up it was unnervingly easy to go in-sim. First time in I had to turn to one of the others and ask what had happened. I thought maybe I’d had a blackout. I couldn’t remember what I’d been doing or what time it was. One of the Russian delegates pointed to my hand. “You know your fingerprints, no? Look at your forearm. You maybe recognize a scar, a mark.” He looked at the back of his own hand. “But distribution of hair is only an average, based on sampling.”

Second time in I had the technicians going when I noticed a peculiar glowing stripe on the cuff of the uniforms. “It’s a red stripe,” explained one of the supervisors, and half an hour into the perceptual tests it became apparent a small adjustment was necessary. The glowing stripe became indistinguishable from the rest of the uniform.

“A slight visual impairment, Mr White.”

“Yeah, I’m colour blind.”

“No need to worry. The neural codes have been recalibrated. You’ll be able to look at the red planet in your accustomed shades of—shall we call it grey?”

In the summer of 2025 we gathered to watch—on a wall screen—the first use of the simularium by the Martians. When the picture came up, they were already in the conference room. Well, I’d seen one pickled in London, hadn’t I? This wasn’t the same thing at all. One of them turned towards the videolink, and said, “Sawn way well big entaw tock.”

“I don’t think we’re quite ready,” said one of the technicians. “Vowel drift in the voice synthesizers.”

It wasn’t the vowels I was worried about. I knew I wasn’t ready. But that’s life. You’re not ready, but it happens anyway.

I always wanted to get into space, but never thought it’d happen. I felt a lurch in my stomach and then I was looking at my hand, dim against a background of bright stars. I wasn’t wearing gloves. It worried me, but I heard the Control voice, close by.

“If you feel any discomfort, simply close your eyes. The floor is beneath your feet. Arm and head rests may be adjusted. Please do not leave your seats.”

And how can I leave my seat, I thought, plugged into a sim-suit? But then—how had I been able to raise my hand?

As the vast glowing disc of Mars rolled into view, I forgot about my seating arrangements and began a slow, bodiless descent toward the surface. A mile or two up, our position shifted, until Mars was below us, and the stars above. An unlikely looking glass flower—a kind of spiral mosaic—was our destination. Only at the last moment—I’d been looking around at the desert—did I realise the articulated mosaic was the simularium, opened out. It hadn’t occurred to me it could do that. Well, I don’t suppose it can, but as we sank into the reception chamber, the gleaming petals began to pick themselves up in a slow swirl and close around us.

I looked round. Bert was sitting with his mouth open. One of the Americans—Russell—got up and clicked the videolink. “Welcome to Mars, gentlemen,” said Garry. “You’ve got the rest of the day and tomorrow morning to get your bearings. The Martians are due tomorrow, so you can relax and make yourselves at home.”

Now Garry, I knew, was maybe a hundred and fifty feet away, in the main control hub on the second floor. I couldn’t quite believe he was talking to us from another planet. But at the same time I knew that if I climbed to the second floor, I wouldn’t find him. And if I set out across the Martian desert and walked a thousand miles I wouldn’t reach him.

Two of the Americans and the Chinese set out at once to find the table tennis tables. The Russians went into a huddle. The rest of us made ourselves familiar with the conference room, or looked out the windows. I found myself anxious not to be alone, and had to remind myself that at any moment there were probably no fewer than three or four dozen pairs of eyes watching every move I made. Who knows how many more would be watching the replays? I couldn’t be less alone if I tried, but I was separated from the rest of the world by this very solid dream of Mars. I tapped my fingers against the glass of the panoramic window.

“Maybe I ought to go out for a stroll before supper,” I said aloud. I felt two light taps on my left cheek, an inch from my nose. Two for no. Someone was awake out there. “Just testing,” I said. Away from the videolink, this was our first line of guidance. One tap for yes, if we were doubtful about something and needed reassurance. Two for no, or as a warning. Continuous tapping meant don’t do anything, don’t say anything, don’t move. Try to stay calm. It might be something as simple as a question raised, ex-sim, about the propriety of some of our responses. Or a breach of security. Or the outbreak of war. We wouldn’t know till they got us out. If they got us out.

I’m not saying there weren’t reasons to be nervous, but I got a good night’s sleep, and woke feeling refreshed. I checked out the breakfast menu. There were some concessions. I got a decent cup of t. The m sandwich was a disappointment, but I’ve tasted worse muck.

At the briefing, we were told the Martians were in the building. I’d had visions of them walking across the desert on their stilts or coming in through the roof like we’d done; but no, they were “here” already. We hadn’t bumped into them last night because our two versions of the simulation hadn’t been merged. Now they had. From now on we’d be sharing the same virtual space. They’d be waiting for us in the conference room at two o’clock. They had no intention, at our first meeting, we were told, of appearing to “invade” a room we’d settled in.

In the event, we didn’t find it so easy to invade the conference room. Russell looked at his watch and pressed a stud. The door slid gently open. It was broad enough to let all of us enter at once, but we didn’t. There were Martians in the room, five of them, and none of us moved. They were about thirty yards away. The one in the middle raised itself slightly on its articulated chair, and said, “Please enter, when you’re ready.”

And this, if you don’t mind me saying, was my moment of glory. “Ready when you are, mate,” and into the conference room half a step ahead of anyone else. But anyone who says I scampered into the room like a trained pup is a liar.

If you’ve never come face to face with a Martian, I’m not sure how to give you an idea of what we felt. The fact we stand taller than they do doesn’t count for much. Their reach is longer. They wear a long history, and look at us, when we’re in front of them, from very far away. But we got used to their physical appearance quickly enough. The first Martians who landed on Earth were under stress. They were sick. In the circumstances, they made a bad impression. These five were healthy. Within the simulation, they were breathing a controlled atmosphere and operating under their own gravity. We had Earth conditions, of course. They still looked as though they ought to be ungainly, but moved around very nimbly in their walking chairs.

We didn’t exactly get a welcome speech—they don’t go out of their way to be polite—more an introductory lecture on conditions on Mars. Very interesting, but I was so wrapped up in watching them that I was only half-listening. They didn’t use their tentacles expressively but, to look at them, you’d have thought they were actually speaking whichever language we were hearing. Sometimes three would speak at once—the simulation allowed us to tune in the language that suited us, and tune out the others—but later, in the exchanges, they replied to whichever language was used, then supplied a translation if wanted. There’s no question they’ve mastered our languages, but that rubbery beak of theirs is ill-adapted to some of our vocal forms. Their flawless diction was down to the vocal synthesizer.

After an hour we were getting restless, because the first beak had barely drawn breath, but then they offered us a guided tour. I got a tap on the cheek. Someone in our viewing audience wanted to see the show, so down we went into the basement to get some idea how the Martians lived. A bit cramped. Limited resources offset by efficiency and strict population control. Of course, we saw what they wanted us to see. Virtual technology at the service of their intellectual endeavours. “Indeed,” our guide told us, “in the same way you now visit our sub-surface dwellings, so, in our simulations, we have explored your planet.”

Back upstairs, we didn’t do much more that day than confirm the structure and timing of the next meeting. One question that did get asked was: why bring us to Mars?

“Because so long as there was an appearance of conversing with you on Earth, we knew we would encounter hostility and resistance. At this remove, you are less at the mercy of your visceral responses.”

“We have an audience of more than a thousand right at this moment,” says Russell—good for him—“all rooted in the soil of planet Earth.”

“That’s as it ought to be,” says the Martian. “No doubt there shall be more in time. But you act as intermediaries. What we say in this meeting need not be constrained by the circumstances of our history.”

Maybe not, but next day the first question they ask is what are the obstacles to establishing cultural and trade relations?

We don’t trust you.

Well, it’s the can of worms we’re here to open. They know the answer as well as we do, but they want to hear us say it, so we do. One, they attacked us. Two, they treated us like animals.

“A regrettable expedient,” says one, “but, in the circumstances, we had little choice but to be deliberate in what we set out to do.”

And that’s when it comes home to me the Martians we’re talking to were alive at the time of the original invasion. We don’t live as long as they do. Doesn’t mean we forget what happened, so naturally the subject of their feeding habits comes up. In their own controlled environment, they insist, their foodstuffs are largely synthetic and vegetable in origin.

“What about the remains of humanoid bipeds found in your cylinders? Weren’t they carried to Earth with the sole purpose of being killed and eaten on the journey?”

This, they protest, is a grotesque misconstruction. “Those bipeds, so-called, are amphibious. On our home planet, they rarely leave the water. They’re mainly farmers and technicians. They are entirely dependent on us for their existence, and served on the expedition as pilots. They had no expectation of surviving the landing.”

You can take that with a pinch of salt if you like, but there’s a case to be made the Martians we know developed originally as marine animals. They never developed the wheel, and the positioning of their tentacles doesn’t make sense on a land animal, no matter what some authorities say.

Leaving aside the question of how they treat their own inferior races, we know how they treated us. “Even if we allow,” says Bert, “that wholesale killing is bound to take place in times of war, we call it a crime when the victims of war, or those in the power of the victors, are killed for sport or amusement.”

The Martians refused to accept such incidents had taken place. Our conviction that they had, they said, was founded either on a misunderstanding, or on fabrications—natural in the circumstances—prompted by fear and hatred.

“Natural in the circumstances,” I agreed. “You killed without warning. Some of us were hunted down as we made a run for it. In places, we were subject to blanket extermination.”

“What we attempted,” said one of the Martians, “was indefensible. We do not expect it may be excused or forgotten. Those who undertook the ‘invasion’ perished, but we are of their kind. We inherit the responsibility for their decisions.”

Acceptance of responsibility was something. But it wasn’t exactly an apology.

Exhaustion of their basic resources might have left the Martians with a weak bargaining position, but anyone who thought we’d be able to name our own price was extensively disabused. The Martians don’t see it that way. We sat and listened as they explained that to give us whatever we asked for would simply distort the inequities and instability already inherent in our own primitive economic arrangements. “How,” they asked us, “are you to estimate the value of a knowledge that must transform the way you live? Only by gauging the ways in which you wish—or imagine you wish—your lives transformed. But, really, your sense of values is little more than a mirage. Your record of anticipating the cultural transformations resulting from development of knowledge or technique is, to say the least, poor.”

Needless to say, that’s not how we saw it, but if the Martians have their way, they’ll be doling out the crumbs from their table, on their terms, in exchange for everything they need. And that’s how it’ll be for the next million years.

Of course, we weren’t in this meeting to make anyone’s decisions for them, but we couldn’t help wondering what kind of a three card trick the Martians were playing. All we got from the videolink was you’re doing a great job, the sim’s working fine, coverage is excellent, we’re getting some great stuff, keep at it.

So we’re a week into the talks, and I’m at one of the observation windows after the day’s session, looking out at the Martian desert, when I hear a rubbery padding behind me, and I feel my scalp prickle. “I wonder, Mr White, whether you’d be willing to talk.”

“It’s what we’re here for,” I said. But I’d never heard one of them using first person singular. I turned.

“Just the two of us,” it said.

Up to now there’d been a few informalities exchanged as we left the conference room, but we rarely bumped into the Martians in the corridors. I was used to looking at them, but I’d never been quite so close. And I’d never been put in a position where I had no choice but to look into those big, dark eyes.

“I’m not sure it would be appropriate,” I replied. I was playing for time.

“I leave it to your discretion,” said the Martian.

I was under no illusion this was a casual invitation. There was always a nagging fear, in-sim, that the Martians might find a way to block the warning signal, but I got a tap on the cheek. One for yes. I wasn’t sure I was being encouraged to talk or to use my discretion.

“Would you be more comfortable if you sit?” it asked. I say “it”, but the Martians are all genetically female. We used to think they had evolved without two sexes, but we know now that at some point in their history they decided one of the two was unnecessary. Bert always insisted on using the female pronoun. I found it easier not to think of them that way.

“Thanks, I’ll stand,” I said.

And how many of the others, I wondered, are being cornered right now, and subject to individual interrogation? After a moment’s thought, I said, “If you want a private conversation, is it wise to do it out here? Anyone might walk in on us.”

“This is not a private conversation, Mr White, as you well know.”

It knew what I was asking, so what? I got a reassuring tap on the cheek. But, far from being relaxed, I was acutely conscious of performing for an unseen audience. My big day, I thought. Biggest day of my life. I wanted to know what it was about, so I asked.

“We’ve observed you as a species,” it said, “studied your history, analysed your cultural productions. Here, at last, we’re able to converse. But the context of a diplomatic exchange imposes constraints. We needn’t deceive ourselves concerning the artificiality of the situation, but we’d welcome the opportunity of speaking with you more directly.”

I’m a bloody performing monkey is what it means.

“Why me?” I asked. “I’d’ve thought Bert’s your man for this kind of thing.”

“We’ll be interested to speak with Monsieur Mevel, but we have a special interest in you. You were born close to the site of our first landings. You feel that you were attacked, even though you were not yet born. When you were younger you knew people with memories of that time. You’ve read the accounts of survivors, and heard their stories repeated by their children and grandchildren. As a consequence, we have a particular interest in how you react to us.”

“Why should you care?”

“Because, notwithstanding your personal history and your geographical origins, we think you may be able to understand how we came to do what we did.”

“That’s not so hard,” I said, looking out the window again. “Your atmosphere’s all but gone and, despite your best efforts, your supply of usable water’s diminishing year on year. You thought you’d come over to our place.”

“Something we might have done at any time over the past fifty thousand years.”

“So why didn’t you?”

“For all its riches, your planet is not our home.”

“Sentimental, eh?”

I wouldn’t have put it past the beak to know I was being sarcastic, but, if it did, it wasn’t for letting me know. “No,” it said. “Settled. We’ve watched your planet. For the most part we respected the integrity of its development, and we took the view that, while your cultures are primitive, you were nevertheless on a trajectory which might yet have allowed the constitution of some rudimentary form of civilization.”

“By which you mean we’re not there yet. That’s not very complimentary,” I pointed out.

“There’s no need to be complimentary about your achievements. You bear the burden of your biocultural limitations. We can hardly expect a group of undereducated savages, possessed of language but prey to a thousand uncertainties, to establish a stable, well-ordered culture. These convulsions are far behind us. We were aware, as we watched, that your actions followed, naturally, the slow evolution of your primitive linguistic pluralities. Because of that, we looked on you as merely the precursors of what you might become, and left you to the difficult and prolonged course of your development.

“More recently, another view took shape among us. We, no less than you, are the product of a long and difficult development. We are not divorced from the struggle for existence, though we have the advantage of long experience in managing that struggle. Why, then, some among us argued, must we make the mistake of supposing ourselves observers only, and above the fray? Remote from us as you are, might we not allow our actions to be informed by considerations you also would recognize?”

It wasn’t my place to answer its rhetorical questions, so I bit my lip.

“It may surprise you to learn,” it went on, “that few of us accepted this. But the observation that you were entering a dangerous phase of exponential technological advance, at a time when we were forced to accept that our planet could not much longer sustain us, lent weight to the arguments of those who intended action. Within a century or two, they pointed out, if these brutes do not first destroy themselves, they may lay waste to their habitat. If they do, is it not the waste of an opportunity? Not only theirs, but ours? We shall expire one day. They may expire before or after they fulfil their potential. In the end, all shall be equal. But today we need not perish.

“At that time, we couldn’t speak to you. Now you may listen, but a century ago most of you had no idea there might be life beyond your planet. Most of us continued to hold that you ought to be allowed to continue your struggle toward civilization. Those who proposed the expedition were determined to act. Many of us were opposed. But that opposition does nothing to limit or lessen our complicity.”

Frankly, I didn’t think this held water. Did they really think we’d let ourselves be talked into accepting the invasion had been planned and carried out by a minority? “Could you do nothing,” I asked—and if you listen to the recording you can hear me hesitate, because I didn’t buy it. Of course they could, if they’d wanted. I wasn’t prepared to believe that a small handful of bad Martians had started the war. It was ridiculous. “Could you do nothing,” I asked, “to stop those who were determined to act?”

“On what grounds might we have taken action against them?”

“On the grounds they were about to commit an unprovoked act of war. You say a majority of the population were opposed to this act of aggression.”

“The last time the actions of one group provoked the counteraction of another, you had not begun to walk upright. We act by the assent of all. If there is disagreement, we do not act. We talk.”

“Yet, in this case, some of you decided to act.”

“The inevitability of our two planets being brought into relation exposed our shortcomings. We were unable to dissuade those who would act. Accepting the intervention would take place, we gave our assent.”

“To an interplanetary crime? Why would you do that, if you thought it was wrong?”

“The other view was not without justice. The principle is simple. Aggression is impermissible. If any one among us were to commit a hostile act against a neighbour, that individual might be stopped by any one of us, and would be stopped, of necessity, by universal assent, as a danger to our society.”

“I don’t see it. You say they’d be stopped. And yet you say, if there’s a disagreement, you do not act. How, then, can you act to stop the aggressor?”

“When our culture attained maturity, there was no longer the need. The example is purely hypothetical. All of us understand and accept the principle. It doesn’t happen.”

“But it did. Are we not your neighbours?”

“As our neighbours, of course, you fall under the protection of this principle.”

“Except that, when push comes to shove—and you need what we have—self-interest takes precedence.”

“It’s no surprise to hear you say that. We take another view. Acts motivated by self-preservation are inevitable, but to imagine them thereby justified is self-deception. A society which accounts self-preservation an adequate excuse for its actions is improperly constituted. A society is not a self, therefore the preservation of society cannot depend upon acts of self-preservation. Only in extremity may such acts be expected, when societal structures have broken down.”

“You’re suggesting the attack on Earth came about as the result of a breakdown in your society?”

“Not at all. If I’m starving, and my neighbour has food, my actions devolve only upon my character. Of course, I’d be very surprised if my neighbour would allow me to starve.”

I thought I could see where this was heading. We are to be good neighbours, and not allow our would-be conquerors to starve.

“But if we,” it went on, “—the members of our society—are starving, while our neighbours have food, we are not in a position to decide, as a society, that we ought to rob our neighbours. Alternatively, how we act may depend on what our neighbours are doing.”

“As I see it, we were minding our own business.”

“Only because of the limitations of your technology. Shall we go for a stroll?” suggested the Martian. “Outside.”

“I hear the air’s rather thin on Mars.”

“You’re not on Mars, Mr White.”

True, but I’d got a warning not to go outside the first day we arrived. I half expected the same now. It didn’t come. So I followed the Martian into the “airlock”. Like a mouse, putting its head warily into a trap.

My first surprise was not that the outside was so big. I’d been looking out the windows, and the initial descent had demonstrated the power of the simulation. But, as the Martian had said, I wasn’t on Mars.

At least, not Mars as we know it, I thought.

It appeared to be a city, of sorts. Or a vast industrial complex. The sun was bright, and very hot. The simularium was behind me, a broad river in front of me. Along the banks of the river were long, low structures that might have been warehouses or factories, all connected to one another by large pipes.

The second surprise was how familiar it seemed, and before I knew what I was doing, I turned and was looking along the Thames toward Tower Bridge.

It wasn’t my London. There were a few towers, but it was a lot flatter than it ought to be. Across the Thames I saw the Sky Garden, and to the right of it the glittering swollen cone we call the Gherkin—familiar landmarks rising out of a mat of unfamiliar structures, all gleaming in the sun. Above them thin ribbons which might have been rails or pathways.

I looked down at the Thames. The water was very clear, but reflected a sky so deep a blue it looked like twilight, though the sun told me it was two or three on a summer afternoon. High in the air, something like a floating platform drifted by, silently. And interlaced between the buildings, lush vegetation. But what colour is it? It’s not green.

On a walkway twenty feet above my head I saw a group of people. They had cameras. Tourists? A Martian was drawing their attention to something, pointing with a tentacle. I knew, then, I was looking at the future.

“All who participated in the initial incursion perished,” said the Martian beside me. “They paid for their actions with their lives. All they had to hope for was extinction and possibly, what is worse, failure.”

“And the contempt of those who remember what they did?” I felt two light taps on my cheek. A warning not to be reckless.

“The contempt of the survivor matters not at all to those who are extinct. We may judge their decisions to have been wrong, but we accept their actions were, as you might say, selfless. They hoped to maintain and to reinvigorate a culture whose history is vastly longer than any of your flimsy, faltering efforts.”

By behaving like barbarians. But this time I didn’t say it.

“They selected an island of a convenient extent, in a temperate region, as an area that might be defended. Admittedly close to a much larger landmass, but not one in which the population has exhibited for an extended period any great unanimity of purpose. Once they were established, they reasoned, the natives would make an accommodation...”

Not tourists. Business partners.

“All very shiny,” I said—though it seemed depressingly quiet and underpopulated. I resented having this vision of the future superimposed on my home. “But you must know we’ll see it for what it is. Propaganda.”

The Martian made a small and brief inflation of its form, which I’d learned to read as a kind of neutral assent—a shrug.

“Propaganda is unnecessary. It was never our intention to sweep out of existence the human species.”

“We never got the idea it was. Apart from anything else, there’s your unfortunate appetite for human blood.”

“There’s no need to play the fool, Mr White. We’ve explained that our nutrients are synthesized. Is it not obvious the members of the expeditionary team were faced by an urgent need to accommodate the many micro-organisms in your biosphere? They made of their bodies living laboratories, in an effort to build up resistance.”

“Yet they were unable to do so.”

“A matter of time, nothing more. Look up at the sky. Notice how deep is its colour. After a hundred and ten years our purifiers... would have done their work.”

“It’s a bit dark.”

“And very clear. According to you, when we attacked, you were minding your own business, Mr White. We know. We were watching. It was said, at the time, that the British had an empire on which the sun never set—which is to say your nation’s wealth depended upon its business operations all across the surface of your planet. That business was founded on the premise that wherever you found what you wanted, it was yours for the taking. If you could take it. You were hardly unique in this attitude. As the Europeans extended their operations into the African continent and the Americas—and began exporting their population to the latter—the results were the same: dispossession of native populations, their exploitation, their enslavement, in some cases, their eradication. Not long before we made our landings, the Europeans who had overrun the North American continent—”

“We call them Americans now.”

“Of course you do. And shortly before we arrived, having already subdued and reduced the native population within the areas they controlled, they were busy slaughtering the inhabitants of what you call the Philippine Islands. No, Mr White, your record of minding your own business tells against you. And given the technological acceleration we had already observed, it was not unreasonable to suppose you might soon be minding your own business on your neighbouring planets.”

“Your attack was a pre-emptive strike, then?”

“By no means. We had our concerns, of course. You are troublemakers. Not by virtue of your nature, as a species—which may be altered, as you will—but according to the weakness of your cultural formulations, your lack of deliberation and responsibility. It’s not that you can’t help yourselves. You choose not to help yourselves. Had you existed on our planet, we would almost certainly have been obliged, by force of necessity, to exterminate you, both for the sake of our own safety and in the interests of planetary hygiene. You are—at the present stage of your development—a foul and obstreporous pest. Please do not take this personally, Mr White. I am speaking in the most general terms.”

And you ain’t helping yourself, mate. I can’t see this playing well to our audience.

But I felt something. And when I looked down, I saw a tentacle resting lightly on my wrist. I had to remind myself I was somewhere else, snug in a sim-suit—that I wasn’t really being touched by a Martian.

“Had you attacked us,” it went on, “which you would certainly have done had you had the means, we would have taken defensive measures, or warned you off.”

I think I made a face at this. To my very great relief, it removed its tentacle from my wrist and said, “I regret that you feel you’ve been insulted. Of course, you did not attack us, Mr White. We attacked you. That is why we are having this conversation. We thought you might understand.”

I was tired of being told I didn’t understand, so I said, “All right. We might have done the same in your position, so what?”

“It’s of no concern to us,” it said, “that you’d have done the same thing. Your actions are of no account. You are irresponsible creatures. Individually and culturally, you are almost beyond the guidance of rational moderation. All we hoped was that you might understand how we came to our decision.”

“Yeah, I get that,” I said. “You did us the honour of accepting our own standards of behaviour before dropping by for a visit.”

“Thank you, Mr White.”

“And now? Have you finished lowering yourself to our level?”

“Quite finished. Since there is no longer any need, let us keep each to our own standards. You may return to your quarters.”

It sounded like a dismissal. I was minded to argue, but I felt two taps on my cheek, so I swallowed it. It made me sick to do it. I watched as the Martian whirled on its seat and headed back to the simularium. I started after it, but was halted by another two taps.

If not back to the simularium, then where?

“Across the river,” said the Control voice. It wasn’t Garry’s voice, but it was familiar. As if I’d been hearing it all my life. “You know the way,” it said.

And I did. I walked over to the pier—I knew better than to try to cross at one of the bridges—and waited for the skim to appear. I cast a glance back at the simularium, glinting in the sunlight against the dark sky, like a slightly dishevelled stack of glass discs. I looked across the river at the top of the Gherkin. They were like palaces in some tale from the Arabian Nights. And as I looked across at the Sky Garden, I thought, Not for the likes of me. Not for a million years.

Several other people made the crossing at the same time. I picked on someone who looked alert, and stood in front of him. “I’d like to be excused,” I said. “I’m not comfortable in this simulation any longer.”

He was about my height, and he looked straight at me. He had light blue eyes and a sharp nose. I got the impression he was making a quick calculation. “Don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said, and moved to the other side of the skim. Turned his back on me and looked downriver. Pretty much as I expected. No talking except in designated areas.

But I’ve been inside one of those glass palaces. And I talked with a Martian.

Nothing to be proud of, I know. I wasn’t feeling very cheery as I headed back to barracks. They say the deep breathing’s good for us, but the air’s so clean it scours the lungs, and I was tired. Hungry too, but I had no appetite for the muck they let us eat. I’d been somewhere else—in some impossible future where somehow the Martians had miscalculated and their plans hadn’t come off—and I’d wakened from a dream in which the whole of my life was different. How can I describe what that dream felt like? As if the yoke of history had been lifted from my shoulders.

But as I trudged along the pedestrian channels, and caught sight of the silent sentinel on Primrose Hill—a vast tripod gazing down with unwinking eyes—the last traces of the dream faded, and I knew myself again for one of the defeated and dispossessed.